Chinese Rifle Treatment

Roy Chapman Andrews and his Adventures in China and Mongolia

Roy Chapman Andrews has been described as "the inspiration for Indiana Jones." That isn't exactly right, but it's close. Andrews' job title was naturalist, formally a zoologist, but his avocation was explorer and adventurer. He is best known for leading a series of expeditions into the Gobi Desert between 1914 and 1928. They searched for fossils and hunted wildlife through what today is northern China and Mongolia but at the time was loosely controlled and contested by China, Mongolian warlords, and the newly forming Soviet Union.

Along the way, in 1925 he documented a Chinese treatment for rifles rendered ineffective by bad karma. Lao Chung was one of his locally recruited workers. They were hunting for samples of the local wildlife, especially the eastern Himalayan goat-antelope known as the takin, known to science as Budorcas taxicolor.

Three days in Sianfu were few enough, but both of us

had so much to do in Peking that we could not linger.

A month later our two hunters returned to Peking from

Ta Pai Shan with a glorious bag including three takin.

Lao Chung attributed their luck to the powers of

an old man named Wang.

When I left Lingtai-miao I gave Lao Chung a rifle

that had never been used.

He said that after several unsuccessful days, when he

had wounded animals but could not kill them,

Wang told him that without doubt he had failed because

the gun had killed a man.

No rifle that had killed a man was good for hunting;

it would have to be "treated."

Wang announced that he would prove to the satisfaction

of everyone that the rifle had taken human life.

He produced three pieces of bamboo, round on one side,

flat on the other, and each perforated with nine holes.

If the gun had killed a man, the sticks would always

fall with the flat sides up when he threw them in the air.

Sure enough they did.

The weapon had certainly killed a man.

In the "treating" process old Wang traced characters

on the barrel with his fingers and then stroked the

rifle from muzzle to butt, mumbling incantations.

In order to prove that it was now in proper condition for

hunting purposes he said he would throw the bamboo sticks

again.

The first time they would fall with both flat sides up;

the second with both round sides and the third with one

flat and one round side uppermost.

The sticks were thrown and fell as predicted.

"Then," said Lao Chung, "I went out immediately and killed

a wild boar with the first shot.

I had no more trouble."

Lao Chung told us also a strange tale about our

first takin hunt.

He said that the man Liu who had performed a sacrifice

at our camp on the Ta Pai Shan, the day we found takin,

was one of a few men who had the power to "open" or "close"

the mountain.

When it had been closed all the game left at once;

when it was opened all the animals came back at once.

On this last takin hunt, Lao Chung had had no success

until he found Wang, the one who had "treated" his rifle.

This old man, like Liu, had the power to open the mountain,

and when he had been persuaded by Lao Chung to accompany

him on a hunt, he gave a remarkable demonstration of

his magic skill.

He wrote several characters on three strips of yellow

paper, rolled them up and buried them.

Then, lighting sticks of incense, he chanted strange words

and the mountain was open.

Lao Chung never failed to find game when he was with

the old man Wang.

After each hunt the mountain was closed by a similar ceremony.

It was useless then for anyone to hunt,

because the game all departed to unknown regions.

Wang and the few others who had this power were

unpopular with their neighbors.

Lao Chung firmly believed all this.

Like most Chinese of the peasant class, he had a simple,

superstitious, highly imaginative mind and would tell

the most astounding stories in such a way that you

could not possibly accuse him of lying.

I remember an instance connected with the first

takin hunt.

After I had killed the cow, I went down the mountain,

hunting for wounded animals.

While I was gone, Lao Chung suddenly came upon the dead

animal and, I presume, was somewhat startled.

Immediately his imaginative brain set to work, and by

the time I returned he had a story ready.

He announced that the takin was wounded, had charged

him and chased him up a tree.

"But," I said, "I know the wild cow was dead for I

killed him myself."

That made not the slightest difference and he

stoutly maintained that the animal had not succumbed

until after it had treed him.

He has dozens of other wonderful stories which he

tells to admiring friends.

Neither Jason nor Tartarin de Tarascon could outdo

Lao Chung!

Wang seems to have misplaced one bamboo stick during his ritual.

Roy Chapman Andrews

Andrews was born and grew up in Beloit, in southern Wisconsin. He spent much of his time outdoors, hunting and shooting. He became a skilled marksman and an enthusiastic self-taught taxidermist. He made enough money through taxidermy to pay to attend Beloit College.

His dream was to work at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. That museum had been founded in 1869 by a group including Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., a very successful plate-glass importer, philanthropist, and the father of the 26th U.S. President.

In the early years of the 1900s, Andrews applied for work at the museum. He was told that there were no non-menial jobs available, so he took a job as a janitor in the taxidermy department. He worked as a janitor, collected specimens for the museum, and studied at Columbia University where he earned a Master of Arts in the study of mammals.

Andrews' overseas adventures began with a 1909–1910 cruise through the Philippine Islands and surrounding regions on the USS Albatross. This iron-hulled twin-screw steamship belonged to the U.S. Navy and is considered by some to be the first specially built marine research vessel.

In 1913 Andrews joined the owner of the USS Adventuress, a 133-foot schooner, on its maiden voyage to Alaska and nearby Arctic waters. They hoped to capture a bowhead whale, an ambitious project which did not succeed. But during a stop on the Pribilof Islands, Andrews captured the best moving picture footage to date of fur seals. This film was of scientific value and it also led to support of the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention of 1911, restricting hunting in the area.

Yunnan province within southern China.

Andrews married Yvette Borup in 1914. She accompanied him on many of his trips. In 1916–1917 the two of them led the museum's Asiatic Zoological Expedition through the ruggedly mountainous Yunnan and other provinces of China. They described the expedition in Camps and Trails in China: A Narrative of Exploration, Adventure, and Sport in Little-Known China.

In 1920, Andrews set his sights on Mongolia. It was theorized at the time to be a rich source of fossils of dinosaurs and ancient mammals (which it was) and the origin of mankind (not so much).

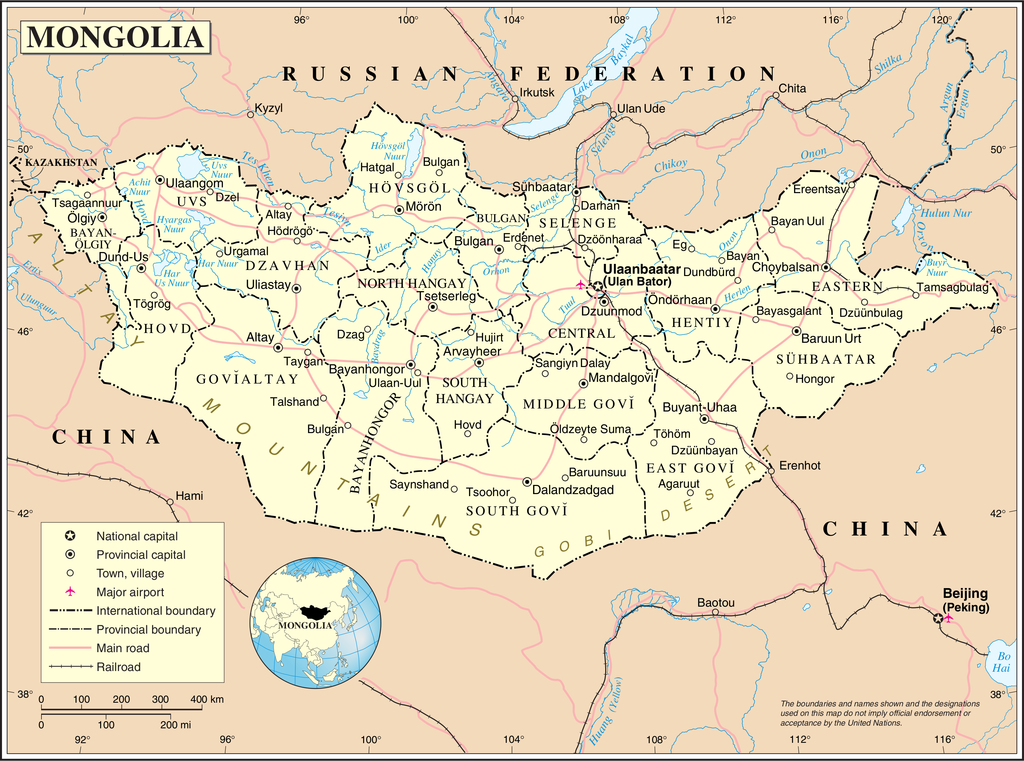

Mongolia

Mongolia is the world's second-largest landlocked country after Kazakhstan, and even today after a booming fertility rate (estimated at 7.33 children per woman in 1970-1975) it is still the world's most sparsely settled independent nation. There are just 4.8 people per square mile, less than Namibia and Western Sahara. Like those two, it is largely desert.

Mongolia came under the influence of the Tibetan Empire in the 7th to 9th centuries AD, with the Uyghur Khanate controlling much of the territory of today's nation of Mongolia at that time. A chieftain named Temüjin finally united the Mongol tribes across the region from the Altai Mountains in the west and Manchuria in the east.

In 1206 he adopted the title Genghis Khan and began a series of ferocious military campaigns that swept across much of Asia and formed the Mongol Empire. It was largest land empire in the history of the world, extending from today's Ukraine in the west to the Korean peninsula in the east, and reaching north into Siberia and south to Vietnam in the southeast and the Gulf of Oman in the southwest. Genghis Khan's Mongol Empire covered 22% of the total land area on Earth and encompassed over 100 million people.

Much like Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan's empire was divided at his death into four khanates which did not come close to the original empire individually or collectively. The Great Khanate was made up of the Mongol homeland plus China and it was the most impressive of the lot. It became the Yuan Dynasty under the rule of Genghis Khan's grandson Kublai Khan. It lasted over a century, but it was replaced by the Ming Dynasty in 1368. The Mongol court fled north into their homeland, pursued by Ming forces who sacked the Mongol capital of Karakorum.

Tibetan Buddhism became a larger influence over Mongolia in the 16th and 17th centuries, with the last Mongol Khan, Ligden Khan, dying in 1634. By 1691 all of today's Mongolia had been incorporated into the Manchu people's Qing Dynasty.

Bogd Jivzundamba Agvaanluvsanchoijinyamdanzanvanchüg was born in 1869 in the family of a Tibetan official.

Bogd Khan of Mongolia as a young man.

He was officially recognized as the new incarnation of the Bogd Gegen in the Potala Palace in Lhasa by the 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso, and the Panchen Lama. He was the eighth Jebtsundamba Khutuktu or Holy Precious Master, the Bogdo Lama or top-ranking lama and spiritual head of the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" school of Tibetan Buddhism in Mongolia. This made him the third ranking leader of Tibetan Buddhism after the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama. He arrived in Urga, the capital of Outer Mongolia, in 1874.

Mongolia declared its independence on 29 December 1911 when the Qing Dynasty fell, ending 220 years of Manchu rule. Bogd Jivzundamba Agvaanluvsanchoijinyamdanzanvanchüg, the Bogdo Lama, was enthroned as Bogd Khan. An independent Mongolia began a fairly short existence.

The Russian Revolution began in 1917. Chinese troops occupied Mongolia in 1919 and the Bogd Khan lost power. In 1920 the White Russian Lieutenant General Baron Ungern entered Mongolia. His troops defeated the Chinese forces in the city later called Ulaanbaatar with the help of Mongol fighters in February 1921. Soviet Russia supported the establishment of a communist government and army in Mongolia, and the Mongolian People's Revolution of 1921 saw Mongolian revolutionaries supported by the Soviet Red Army expel the White Russian forces from the country.

The Bogd Khan was returned to power in a limited monarchy under the effective control of the Soviet Union. He died in 1924 and the Mongolian People's Republic was proclaimed. It was a Soviet satellite state far from Moscow in a time when transportation and communication were slow and unreliable. Soviet influence increased over the years, with the number of Buddhist monks in the country dropping from 100,000 in 1924 to 110 in 1990.

Roy Chapman Andrews in Mongolia

Between 1922 and 1925, during the last years of the Bogd Khan and the establishment of the Mongolian People's Republic, expeditions led by Andrews drove northwest from Beijing in caravans of Dodge cars.

Andrews' expeditions made many prominent discoveries. In 1922 they discovered a fossilized Baluchitherium, a very large hornless rhinoceros (later renamed the Indricotherium) that lived 34–23 million years ago.

What really captured both scientific and popular attention was their discovery of dinosaur eggs in 1923, what were thought at the time to be the eggs of the Protoceratops dinosaur that they also discovered. It lived from 75 to 71 million years ago. The dinosaur species Protoceratops andrewsi and the extinct mammal species Andrewsarchus mongoliensis were named for the expedition leader.

Political unrest prevented expeditions in 1926 and 1927. They returned to the Gobi in 1928, but their finds were confiscated for a while by the Chinese authorities. The 1929 expedition was also canceled.

Andrews' last visit to the Gobi desert was in 1930, when he discovered some mastodon fossils.

From the Gobi Desert to the Typewriter

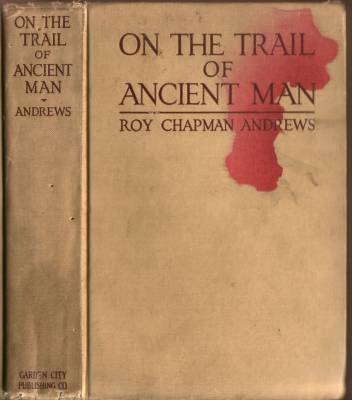

In 1926 Roy Chapman Andrews wrote one of his many books. Some of his writings were academic, like Monographs of the Pacific Cetacea (1914-1916), but most were tales of adventure such as Across Mongolian Plains, Ends of the Earth, Exploring with Andrews, and several more.

One of his books with an emphasis on adventure was On The Trail Of Ancient Man, published in 1926 after the 1922-1926 series of annual expeditions. I purchased a damaged copy through Amazon for just $3.99. I prefer to believe that the stain is from blood, not red wine as the seller described it.

The book has a good overview of the scientific discoveries, but it doesn't get into the detail of the paleontology and geology. It concentrates much more on the adventure and the hunting.

There are many descriptions of how their fleet of Dodge cars are the ideal vehicles for chasing large herds of antelopes across the Gobi Desert. It's like product placement in current movies, I suppose. There are many scenes where curious wildlife bravely approach the machine, and then the explorers start chasing the animals. We are given detailed reports of the running speeds of numerous individuals of varying ages and species.

They did a surprising amount of hunting without even getting out of the car, firing away at animals at medium to long range.

Was Roy Chapman Andrews the Inspiration for Indiana Jones?

In his book Dinosaurs in the Attic: An Excursion Into the American Museum of Natural History, staff member Douglas Preston wrote:

Andrews is allegedly the real person that the movie character of Indiana Jones was patterned after. Andrews was an accomplished stage master. He created an image and lived it out impeccably—there was no chink in his armor. Roy Chapman Andrews: famous explorer, dinosaur hunter, exemplar of Anglo-Saxon virtues, crack shot, fighter of Mongolian brigands, the man who created the metaphor of 'Outer Mongolia' as denoting any exceedingly remote place.

An analysis by Smithsonian Institution writers, however, concludes that the inspiration was indirect. Andrews, Colonel Percy Fawcett, and other explorers were the models for the heroes of adventure films of the 1940s and 1950s. Those characters inspired George Lucas and his fellow writers of the Indiana Jones screenplays.

Other Books by Roy Chapman Andrews

Some of the content of Chapter III of On the Trail of Ancient Man, "Hunting the Golden Fleece", can be read on-line where it appears in Asia and the Americas: Volume 22 (January 1, 1922, East and West Association).

His books Across Mongolian Plains and Camps and Trails in China are available from his author's page at Project Gutenberg.